Three Things We Can Learn From Someone Awarded The Medal Of Honor

Today’s post discusses three things we can learn from a Medal of Honor

recipient.

On 19 March 1945, the USS Franklin, an Essex-class carrier was

attacked just after dawn by a Japanese bomber. She was part of a huge US Navy

fleet called Task Force 58. The bomber dropped two bombs of 550 pounds each

that started a conflagration never seen before or since on a US carrier.

Approximately 400 men were instantly killed on the hangar deck and hundreds more

died from explosions, fire, asphyxiation, and drowning. Observers on other

ships were convinced the ship was doomed, but thanks to the heroic efforts of

its crew and that of other ships assisting her, the Franklin was able to

sail home. Her crew would go on to become the most decorated crew in US Navy

history, becoming the recipients of:

· 2 Medals of Honor, the highest decoration

presented by the US military

· 19 Navy Crosses

· 22 Silver Stars

· 115 Bronze Stars

· and 234 Letters of Commendation

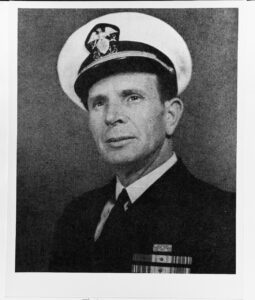

The recipient of one of those Medals of Honor was

Lt. Donald Gary, who entered the navy as an enlisted man and rose through the

ranks receiving an officer’s commission in 1943. In December 1944, he was

ordered to report to the Franklin while she was under repair at

Bremerton, Washington. An engineering officer, he had served aboard the

battleship USS Idaho, the cruiser USS Indianapolis, and the

carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6)

Three Leadership Traits

Before and during the battle, Lt. Gary demonstrated numerous leadership

traits, three of which are relevant here.

Initiative

His battle station was in one of the engine rooms near the bottom of the ship. Without being ordered to do so, he took it upon himself to learn nearly every possible escape route between the

keel and the flight deck. He knew that, if the crew was ordered to abandon

ship, he would need to get his men and himself to safety and that many routes

might be damaged by bombs, flooded by water, or filled with fire. No one

ordered him to do this, he did it on his own initiative.

Decisiveness

His first act of decisiveness came when he heard the explosions. When the

Japanese aircraft attacked, Lt. Gary was just plugging his electric razor in to

lend it to one of his men. The explosions knocked them off their feet. Smoke

filled their compartment, and he grabbed a rebreather (like an oxygen mask and

bottle) and led his men out. They found one route blocked and had to turn

around eventually winding up in the main mess hall (cafeteria) three decks

below the flight deck. Seeing a light in one of the smaller mess halls nearby,

they entered and found 300 others taking refuge there in a dark compartment rapidly

filling with smoke. The officer in charge, a doctor, ordered the men not to

talk out loud, but to pray silently to conserve oxygen. Meanwhile planes,

ammunition, bombs, and rockets continued to explode on the decks above. Lt.

Gary knew that there were other munitions just above where they were and if

those munitions exploded, it would probably kill them all.

Over the next 90 minutes he concluded that they had to get out of that part

of the ship before they were blown up or asphyxiated. He went over various

routes in his mind. He chose one and told the officer in charge, a doctor, that

he was going to see if it would work. He didn’t ask permission, he announced in

a bold voice that he was going to find a way out and that he would come back

for everyone.

Courage

It takes a courageous person to leave the (relative) safety of a room and

venture forth into a dark and burning ship where explosions are still going

off. Taking his rebreather and a flashlight, he left. He soon discovered he had

to back up and go down a deck and then across to air shafts that led to the

flight deck. The heat and smoke almost drove him away, but he kept at it. When

he started to grab the rungs of the ladder in one of the air shafts the hot

metal burned his hands.

Lt. Gary would find his way to safety, then return three times to

successfully evacuate those 300 men. (He didn’t stop there, see his Medal of

Honor Citation below.) He could have gotten himself to safety and abandoned the

men trapped below, but he had given his word to them he would be back.

Had Lt. Gary not rescued those men, they would have died of asphyxiation as

did other men in compartments such as Sick Bay.

Our Takeaway

Here is what we can learn from Lt. Gary. He made it a point, without

being told to do so, to learn every square inch of that 27,200 Essex-class

carrier below the flight deck. [EDIT: Further research indicates that his superior officer advised or ordered him to learn the ship. I am still researching this.] What does that mean to us? In 2003, the Station

nightclub burned in West Warwick, Rhode Island. A Rock band, Great White, was

performing there and their pyrotechnics started a fire that ultimately killed

100 and injured another 230. Most died or were injured when they tried to

escape through the front doors.

There were four exits from that nightclub, Security footage taken that night

showed that most of the people tried to escape through the front doors rather

than seeking out the other exits.

Most of us have never been in a situation as dangerous as Lt. Gary’s but in

today’s world of extreme weather events, active shootings, and other dangerous

situations, we too can practice initiative, decisiveness, and have courage.

Do you make it a habit to know where the exits are in any building you are

in? Ever since I have learned about the senseless deaths caused by the Station

night club fire, I make it a point to know where all the exits are in a

restaurant, movie theater, or other business that I’m in. I do the same on an

airplane. I count the number of rows to the closest exit in case we must

evacuate a smoke-filled plane. I walked the mall near my home, and I made it a

point to learn which doors led outside (I’m not talking about public entrances,

you’ll see unmarked doors such as those below leading to long hallways which

allow delivery people to deliver to the back of stores or employees to move

around “behind the scenes.” Some of these lead outside. The same is true of

banquet hotels.)

Nearly all malls have access doors like these that lead to hallways. They may or may not lead outside.

Knowing your environment and planning how you will react if a danger

presents itself is called Situational Awareness.

Use Initiative

The next time you are in a restaurant, take the initiative to learn where

you are in relation to the nearest exit, which may well be through the kitchen.

If you are in a large hotel or a mall, know that nearly all stores have a back

entrance where you can evacuate through in case of a fire or active shooter.

The mall near me also has some hallways identified as “storm shelters.”

Be Decisive and Courageous

If something does go wrong, get your family and friends moving toward the

appropriate exit as quickly as possible. They may be reluctant at first,

especially if you detect danger before they do. If you see danger, have the

courage to alert them and to convince them to get moving.

I challenge you to practice situational awareness if you are not already

doing so. You just might save your life or a life of someone close to you.

Let’s be careful out there!

Lt. Gary’s Medal of Honor Citation

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life

above and beyond the call of duty as an engineering officer attached to the

U.S.S. Franklin when that vessel was fiercely attacked by enemy aircraft during

the operations against the Japanese Home Islands near Kobe, Japan, 19 March

1945. Stationed on the third deck when the ship was rocked by a series of

violent explosions set off in her own ready bombs, rockets, and ammunition by

the hostile attack, Lt. (j.g.) Gary unhesitatingly risked his life to assist

several hundred men trapped in a messing compartment filled with smoke, and

with no apparent egress. As the imperiled men below, decks became increasingly

panic stricken under the raging fury of incessant explosions, he confidently

assured them he would find a means of effecting their release and, groping

through the dark, debris-filled corridors, ultimately discovered an escapeway.

Staunchly determined, he struggled back to the messing compartment three times

despite menacing flames, flooding water, and the ominous threat of sudden

additional explosions, on each occasion calmly leading his men through the

blanketing pall of smoke until the last one had been saved. Selfless in his

concern for his ship and his fellows, he constantly rallied others about him,

repeatedly organized and led firefighting parties into the blazing inferno on

the flight deck, and, when firerooms 1 and 2 were found to be inoperable,

entered No. 3 fireroom and directed the raising of steam in one boiler in the

face of extreme difficulty and hazard. An inspiring and courageous leader, Lt.

(j.g.) Gary rendered self-sacrificing service under the most perilous

conditions and, by his heroic initiative, fortitude, and valor, was responsible

for the saving of several hundred lives. His conduct throughout reflects the

highest credit upon himself and upon the U.S. Naval Service.

Sources

Lt. Gary: Lucky Lady: The World War II Heroics of the USS Santa Fe and Franklin

The Station Night Club Fire: Wikipedia and YouTube (WARNING: Video is graphic.)

1 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] the Brooklyn Naval Yard in April 1945. Captain Leslie Gehres and others of the crew, including Medal of Honor winner Lt. Donald Gary participated, talking about what they witnessed and did. I was amazed to see Gary, then in his […]