The WW II Alliance Between Germany and Japan

“Our greatest triumph lies in the fact that we achieved the impossible, Allied military unity of action.”1 –General George C. Marshall, 1945

When you look at the history of the Second World War and see the success of the alliance among the Allies, especially the U.S. and the United Kingdom, you may ask, what prevented the alliance between Germany and Japan from being equally effective?

Culture Clash

There are many reasons, perhaps the most important being those rooted in culture. On one side of the coin, the Allies share a common western culture. The U.S. was a former colony of Great Britain and once past the War of 1812 they had an interwoven relationship built on a common language, similar beliefs in freedom, and beneficial trade. Although Stalin’s Russia had a totalitarian government more in common with Germany and Japan, Russia’s culture was, for the most part, western.

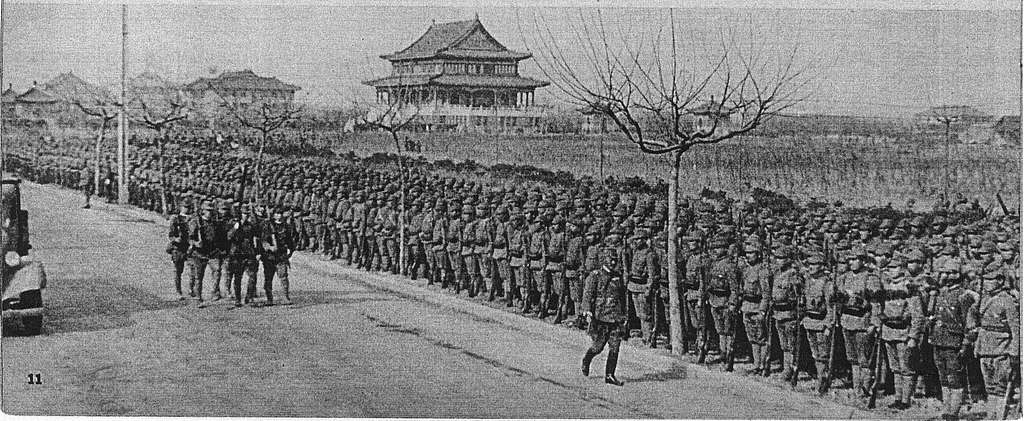

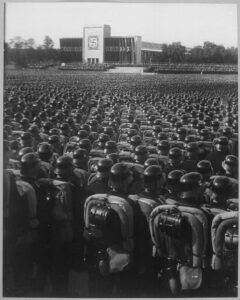

On the Axis side of that coin, Germany had a western culture and was a relatively new country. Japan was an ancient country with an eastern culture. By the mid-1930s, both were governed by leaders who promoted philosophies of racial superiority. Each saw the other as a lesser race.*

In his book, Retribution: The Battle For Japan, 1944-45, Sir Max Hastings writes:

Hitler had no wish for Asians to meddle in his Aryan war. Indeed, despite Himmler’s best efforts to prove that Japanese possessed some Aryan blood, Hitler remained embarrassed by the association of the Nazi cause with Untermenschen. He received the Japanese ambassador in Berlin twice after Pearl Harbor, then not for a year.2

Japan, too, believed in its own racial superiority. Sociologist Hiroshi Fukurai and Historian Alice Yang wrote:

After the Western concept of race was first introduced in Japan in the late nineteenth century, state planners and political elites incorporated its concept to construct a set of “racialized” ideologies to promote a new nation-state building project. These manufactured ideologies included an imagined national unity based on its divine cultural roots in the “three-thousand-year history” of the imperial family, a myth of racial homogeneity of its national subject, and claims of Japanese racial superiority over other Asian races.3

No Shared History

Another reason that prevented a stronger alliance was, that while the Allies had a history of cooperation going back to World War I and beyond, Japan and Germany had no such history. Japan had acquired many possessions in the Pacific after the end of World War II at Germany’s expense. Meanwhile the U.S. and U.K. had been allies in World War I and had created a close working relationship even before Pearl Harbor. This was not just a relationship at the senior levels, in 1940 Lord Lothian, the British ambassador to the U.S., signed a joint memorandum with President Roosevelt creating “the British Science and Technical Mission.” This mission would share information on British advances in radar, aircraft engines, radio location, explosives, and more. The U.S. would adopt British techniques in naval fighter direction as well.4

Japan had a dire need for a portable anti-tank weapon in 1944-45. Such a weapon existed. It was German and called the Panzerfaust. Yet the technology was never shared because Germany and Japan did not have the relationship that the Allies, especially the British and the U.S., had.5

Distance and Timing

Jonathan Parshall was the keynote speaker of the 35th Admiral Nimitz Symposium at the National Museum of the Pacific War which I attended on September 17th. He is the co-author of Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. His keynote put us in the big picture describing the military, political and economic events, and influences of that year around the globe.

During the Q and A session, he was asked about the lack of a strong alliance between Germany and Japan. He responded:

There’s a couple of things that are driving that, first is their physical separation, that is the first main issue. It’s really tough to coordinate forces that are literally half a planet apart.6

The distance between Tokyo and Hamburg by sea is 13,400 miles. Compare that to the distance between New York and London (3800 sea miles) or the distance between New York and Murmansk, Russia (4600 sea miles).7

Parshall’s second point was that the Japanese reached their high-water mark in April and early May 1942. At the same time, the Germans were facing the muddy season in the Caucasus and were still getting over the effects of the battles at Kerch and Kharkov. He also said that the long supply line the Japanese would have had could have been attacked by British air elements on the subcontinent.8 The Germans would have faced a long supply line as well.

Lack of Resources

Richard B. Frank, author of books such as Tower of Skulls, Guadalcanal, and Downfall also spoke at the symposium. He discussed the same topic approaching it from a different direction. In his book, Guadalcanal, he went a little more in depth than he did at the symposium writing:

Although Army strategy surfaced early, it received its clearest expression in a master war plan prepared under the direction of Brigadier General Dwight D. Eisenhower in February 1942. Assuming the safety of the continental United States and Hawaii from direct attack, the Army planners advanced three prerequisites for a successful conclusion of the war: maintaining the United Kingdom, active Soviet participation in the war, and the security of the Middle east and India to prevent a junction of the Germans and Japanese9. (Emphasis mine)

In the symposium, Frank discussed how Army Chief of Staff, General George Marshall, came to support the amphibious landing at Guadalcanal. He did this once he saw that the British would not support an attack on mainland Europe as soon as he wanted. Once he realized that, Frank said that Marshall believed the invasion of Guadalcanal would direct Japanese resources away from linking up with Germany10.

Timing

Frank goes on to say that, losing the Battle of Midway and failing to retake Guadalcanal ended any chance the Japanese could link up with the Germans across the Indian Ocean and into the Middle East11.

Hastings writes:

Only in January 1943, towards the end of the disaster of Stalingrad, did Hitler make a belated and unsuccessful attempt to persuade Japan to join his Russian war. By then, the moment had passed at which such an intervention might have altered history. Germany’s Asian ally was far too heavily committed in the Pacific, South-East Asia and China to gratuitously engage a new adversary.12

Summary

Had there been a stronger alliance established sooner, would Japan have opened a “second front” against Russia? Possibly, of course the Japanese would have to overcome the memories of their devastating defeat at the hands of the Russians in 1939 in the Nomohan Incident.13 If they had attacked Russia in concert with Germany, rather than moving against China, perhaps the war on the Eastern Front would have ended in a different manner knocking Russia out of the war. Germany could have then turned its undivided attention on Great Britain in the days before the U.S. mobilized.

The Free World is fortunate that the alliance between Germany and Japan was nowhere near as strong or effective as that of the Allies. Otherwise, the geopolitical map of the world might be strikingly different. And not in a good way.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

*I acknowledge the Allies were racist. They did not, however, use it as a reason to practice genocide as did Germany and Japan.

1 Overy, R. (1996, March 31). Why the Allies Won (New York: W W Norton & Co Inc. 1996) 245

2 Hastings, Sir Max. Retribution: The Battle For Japan 1944-45, (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition, 2008) 30-31.

3 Hiroshi Fukurai and Alice Yang, The History of Japanese Racism, Japanese American Redress, and the Dangers Associated with Government Regulation of Hate Speech, 45 Hastings Const. L.Q. 533 (2018).

Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol45/iss3/5

4 ETHW. (2016, March 31). The Beginnings of Naval Fighter Direction – Chapter 5 of Radar and the Fighter Directors – Engineering and Technology History Wiki. ETHW. Accessed 09/27/2022, from https://ethw.org/The_Beginnings_of_Naval_Fighter_Direction_-_Chapter_5_of_Radar_and_the_Fighter_Directors

5 Hastings, Sir Max, Retribution 32

6 Parshall, Jonathan, Keynote Address, Admiral Nimitz Foundation, 35th Annual Symposium, 1942: The Perilous Year, Video, 7:06:50, YouTube, 2022, Accessed 09/21/2022,

7 Sea routes and distances, http://ports.com/sea-route/ Accessed 09/28/2022

8 Parshall. 2022

9 Frank, Richard B. Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. (New York: Penguin Books, 1990) 8.

10 Frank, Richard B., Admiral Nimitz Foundation, 35th Annual Symposium, 1942: The Perilous Year, Video, 7:06:50, YouTube, 2022, Accessed 09/21/2022

11 Frank, Admiral Nimitz Foundation, 35th Annual Symposium, 2022.

12 Hastings. Retribution 31.

13 Frank, Richard B. Tower of Skulls: A History of The Asia-Pacific War July 1937-May 1942, (New York: W.W. Norton, 2020) 115-123