Radar’s Role On 19 March 1945

The more I learned about the events of 19 March 1945, the more curious I became. I found myself asking questions I didn’t see answered in any of the books, videos, or articles I’d read. One of those questions was why the USS Hancock, which was stationed one thousand yards or so from the Franklin, was able to see the incoming bomber on their radar when the radar sets on the Franklin could not. That started me off on a research journey.

The Missions

By early 1945, the Allied forces were moving closer and closer to Japan’s home islands. Iwo Jima, an important airbase for the Japanese, was invaded on 19 February. It would take six weeks of intense fighting with heavy casualties, but the U.S. prevailed in the end. The next island would be Okinawa, a much larger island, and Allied leaders knew they needed to reduce, if not eliminate, the Japanese kamikaze attacks on the invading fleet.

In mid-February and again in mid-March, Admiral Mitscher led Task Force 58, now composed of 16 carriers, eight battleships, 16 cruisers, and 63 destroyers. Its missions were to destroy enemy airbases, their aircraft, and port-bound ships in the Japanese home islands and Formosa (now Taiwan). The task force covered 100 miles from end to end.[1]

Bad weather both helped and hindered the February mission. It helped by concealing the task force and allowed it to launch aircraft undetected from sixty miles off the Japanese coast. But the heavy weather hindered target acquisition. Still, 300 Japanese planes were destroyed at the heavy cost of sixty US aircraft.[2]

One month later Mitscher and his men returned, this time with Franklin. In his memoir, Above and Beyond: Marine Air Combat in World War II, then Major Charles Weiland, the squadron commander of VMF-452 part of USS Franklin’s Air Group 5 wrote:

While the task force moved relentlessly on toward Japan, the planning for the Okinawa invasion more than sparked our interest. I sat in on RAdm Ralph Davison’s briefings, and they gave me some inkling of what our job was cut out to be. The invasion was to commence in two weeks, and it was made crystal clear that the kamikaze threat had to be contained first. It was emphasized that this was the most effective and dangerous weapon that the Japanese had to offer.[3]

The Americans arrived off Japan’s coast on 17 March, but, unlike in February, they were discovered by Japanese radar and scouting aircraft before they could launch surprise airstrikes. When the first US aircrews arrived over the Japanese landing fields the following day, they found fewer aircraft than they expected. That was because those aircraft were off attacking the US fleet.[4] Enterprise was struck by a bomb which turned out to be a dud, and three bombers attacked Yorktown with one bomb scoring a hit that killed five and wounded 26 crew members. Meanwhile, Intrepid splashed a kamikaze so close to the carrier that burning fragments from the bomber killed two on board the carrier and started a fire on the hangar deck.[5]

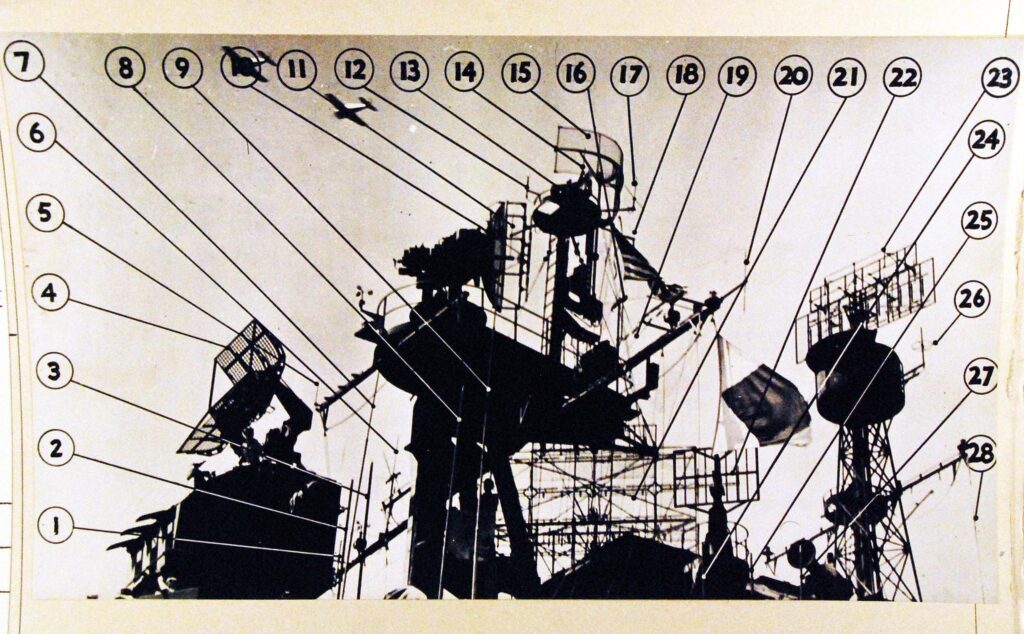

The fleet’s primary defense against Japanese kamikazes and bombers was its fighter pilots and their aircraft. Their strategy was to intercept Japanese “bogeys,” as enemy aircraft were called, as far from the fleet as possible to give the fighters the maximum amount of time to shoot down or otherwise disrupt the attacks.[6] Key to these interceptions was the use of radar. A Combat Air Patrol (CAP) would be alerted to intercept incoming bogeys by the Fighter Director Officer (FDO) stationed in the Combat Information Center (CIC) using air search radar to target the enemy.

Radar’s Imperfections

But radar had its limitations. It couldn’t detect low-flying aircraft or those flying more than 75 degrees above the horizon.[7] A bogey could be lost in the clutter of American aircraft landing and taking off from the carriers and the Japanese used it to their advantage.[8] Antennae arrays could have slight variations in sizes from ship to ship impacting the effectiveness of detection.

That effectiveness was also directly related to how experienced the radar operators and flight director officers (FDOs) were.[9] For many of the crew, this was not only their first taste of combat, but Franklin was the first ship they had served on and their first time at sea.

Experienced or not, lack of sleep could also hinder effectiveness. In his book, Inferno, The Epic Life and Death Struggle of the USS Franklin In World War II, Joseph A. Springer writes that twelve times the crew of the Franklin had been called to General Quarters that night.

While friendly bogies triggered most of these alerts, each deprived the crew of much-needed rest. At present, many of the crew-including department heads and commanders-had been without sleep for forty hours or more.[10]

19 March 1945

And, as numerous crew members would report, it was also cold that morning. Hours before dawn, at 0330, Franklin turned into the wind and shortly thereafter launched her first strike against targets at the Japanese naval base at Kure. She began launching her second strike at 0655.[11]

As the sun rose, horizontal visibility was good, but the skies were overcast with a ceiling of about 2,000 feet.

In a space of 10 minutes before 0700, reports were received on three separate bogeys varying in distance from 20 to 30 miles. The last of the three was reported at 0657 as being 24 miles away and closing. At 0705 the carrier Hancock, a thousand yards away from Franklin reported a bogey but gave no bearing or distance. Captain Gehres contacted his Combat Information Center, but they reported nothing on radar. He told lookouts to keep a sharp watch, then called his forward fire control Director and gave him permission to open fire on any unidentified aircraft without further orders.

Then Franklin’s CIC picked up a bogey 12 miles out and closing, 270° off the port beam, but the contact disappeared in the clutter of friendly aircraft.

Less than a minute later, the Hancock radioed Franklin, that a bogey was at 350° and 10 miles out (almost directly in front of the ship). Captain Gehres said he never got this report. Meanwhile, the lookouts were focused on looking to port. Another minute or so went by and then a Japanese “Judy” dive bomber dropped out of the clouds 1,000 yards in front of the ship. Before anyone could react, it flew down the length of the flight deck dropping two 250 kg semi-armor piercing bombs.[12]

Both bombs penetrated the wooden flight deck and exploded in the hangar. The first may have ricocheted off the armored flight deck and exploded just above it. The second exploded near the gallery deck high up in the hangar and above parked and fueled airplanes.[13]

The fight for the ship’s-and the men’s-survival began.

[1] Charles Weiland, Above and Beyond: Marine Air Combat in World War II (New York: ibooks, 1997) 169

[2] Rod MacDonald, Task Force 58: The US Navy’s Fast Carrier Strike Force That Won The War In The Pacific (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2021) 434-435

[3] Weiland 170

[4] Henry Sakaida and Koji Takaki, Genda’s Blade (Hersham: Classic Publications, 2003) 23

[5] Samuel Eliot Morison, Victory In The Pacific 1945, Vol XIV (Atlantic-Little, Brown; 1960) 94

[6] Clark Reynolds, The Fast Carriers: The Forging of an Air Navy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1968) 221

[7] Norman Friedman, U.S. Aircraft Carriers An Illustrated Design History (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1983) 145

[8] A.A. Hoehling, The Franklin Comes Home (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1974) 27-28

[9] Radar Bulletin No. 1A The Capabilities and Limitations of Shipborne Radar, Hyperwar, Last modified 27 January 2019, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ref/RADONEA/COMINCH-P-08-06.html

[10] Joseph A. Springer, Inferno, The Epic Life and Death Struggle of the USS Franklin In World War II (Minneapolis: Zenith Press, 2011) 194

[11] USS Franklin Original Documents (Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing, 1994) 10

[12]Springer, 196-97

[13] USS Franklin CV-13 War Damage Report paragraphs 3-30, 3-31