USS Franklin’s Connection To The Doolittle Raid

In researching my book on USS Franklin, I learned that there is a connection between the Doolittle raid and Big Ben. Tuesday, April 18, is the 81st anniversary of that raid.

Pearl Harbor had been attacked just four months before, and the Japanese had steamrolled their way across the Pacific. Wake Island and other US possessions had fallen, and news from the Philippines was not good. When planning began in January 1942, American leaders knew they needed some sort of good news to improve the morale of Americans and our allies.

In a 1980 interview, General Jimmy Doolittle said the mission had “three purposes:”

- To give the American public a morale boost,

- It caused the Japanese to question their warlords,

- It caused the Japanese to retain aircraft to defend the home islands rather than sending them to the South Pacific.

Franklin’s Connection

Lt. Commander Stephen Jurika, Franklin’s navigator on 19 March 1945, was the Intelligence Officer on USS Hornet in 1942. An aviator himself, he played a key role in briefing Doolittle and his pilots providing them with anti-aircraft and targeting information as well as teaching them about Japanese culture. He also taught the crews the Chinese sentence “Lusau hoo metwa fugi,” which means “I’m American!” Several of the bomber crews would use this to good effect when they met Chinese civilians. In his oral history, The Reminiscences of Capt. Stephen Jurika, Jr., USN (Ret.) Vol. 1 he’s asked by the interviewer what his initial reaction was when he saw the 200 Army officers and enlisted men that boarded Hornet. He answered:

I think our initial reaction, most of the officers on the ship and certainly the captain’s and mine, was that an all-volunteer crew like this had to be special in ability to fly and desire to do something as a group together. But in looks, in appearance, and in demeanor, I would say that they appeared undisciplined. Typical of this was the open collars and short-sleeved shirts-the weather was quite cool in Alameda-grommets either crushed or none at all in their caps, worn-out, scuffed-type shoes. They were not in flight clothing. These were people who had a chance to stay in the BOQ and clean up and come aboard the ship.”

This is a good example of the difference between the cultures of the Army Air Corps and the US Navy. Jurika was no paper-pusher, he was already one of the best aviators in the Navy. Nor did he lack courage. The following year, he would go on to lead a dangerous patrol behind Japanese lines on the island of New Georgia. His service on Hornet would end with its sinking at The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands in October of 1942. In addition to the Navy Cross he was awarded for his actions on 19 March, he also received the Silver Star, two Legions of Merit, and two Commendation Medals.

Fluent in the Japanese language, he served as an assistant military attaché in Tokyo before World War II. There he spent a great deal of his time observing the Imperial Japanese Navy as well as familiarizing himself with future targets of military interest. Near the end of his assignment there, he was presented a medal by the Japanese government. Not, he pointed out because of services he provided, but in commemoration of some special anniversary. In the picture below, you see Lt. Colonel James Doolittle tying a medal to the tail fin of one of the bombs he would carry in his B-25. In his oral history, Jurika says this was his medal.

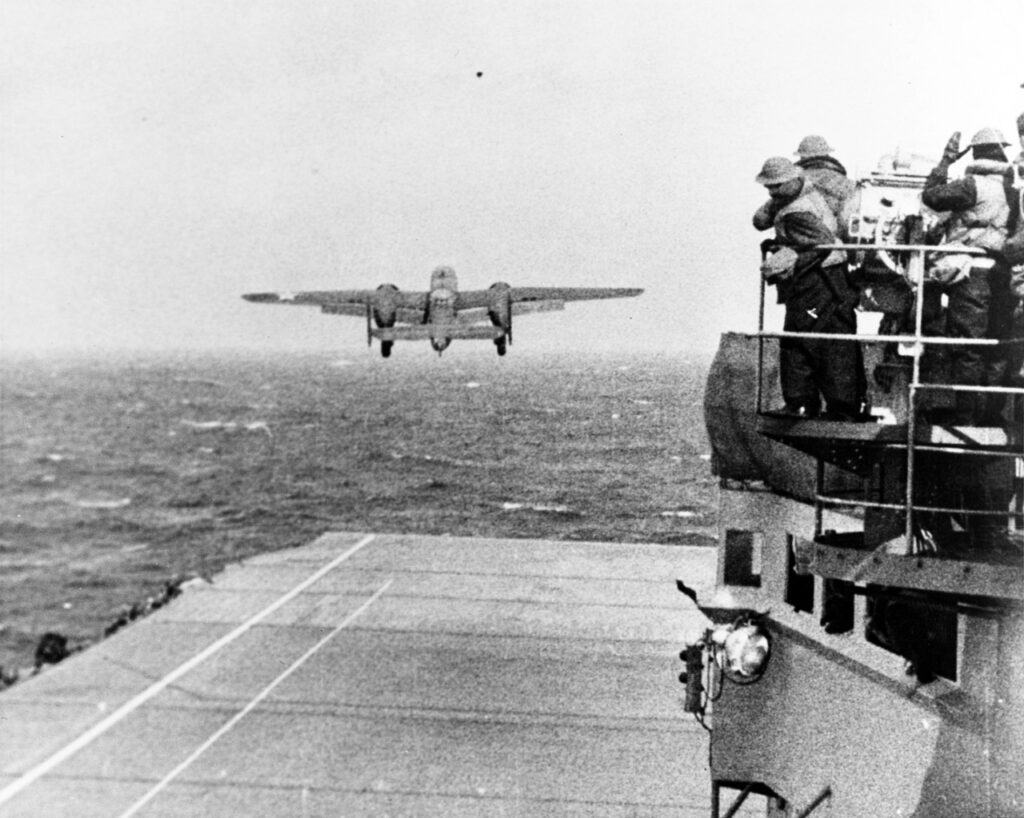

B-25s took off. US Navy NH-102457.

The Doolittle Raid Launches Early

As the Hornet, USS Enterprise, and their escort ships traveled towards Japan, they sighted a Japanese fishing vessel which they took to be a picket ship. Cruisers sank the picket ship and Admiral Halsey, commanding the mission, decided to launch the bombers hundreds of miles earlier than they had planned. The launch went off without a hitch as 16 bombers headed toward Tokyo and other cities.

Jurika was instructed by Captain Mitscher to monitor Japanese AM radio broadcasts to see if any warnings were given or announcements made that bombing had occurred. Others used personal radios or listened to Hornet’s public address system. It relayed reports from the various Japanese radio stations as they reported local news or played music.

Jurika knew when the bombers were expected over their targets, but the time passed with no news of attacks being broadcast. Finally, announcements were made at 2:45 PM several hours after the attacks had taken place. Early reports from Japanese stations exaggerated damage and the number of bombers.

The Raid’s Aftermath

Doolittle and his men would go on to crash-land or bail out along the Chinese coast. (One plane wound up in Russia interred by Stalin for 13 months). Of the crews, three men were killed in action and three died in captivity. Sadly, it was the Chinese population that would bear the wrath of Japanese reprisals. In his book, Tower of Skulls, author Richard B. Frank writes that more than 250,000 Chinese civilians were killed, thousands more raped or wounded while the Chinese Army lost 30,000 casualties trying to stop the Japanese Army’s depredations.

The Japanese reassigned four fighter squadrons to defend the home islands instead of sending them to the South Pacific. And the attack caused them to focus more on their defensive strategy which culminated in planning and losing the Battle of Midway.

Once Doolittle’s men returned to the US, Doolittle would be awarded the Medal of Honor and would later command the Eighth Air Force, Fifteenth Air Force, and Twelfth Air Force.

Ruptured Duck pilot Ted Lawson, who had his left leg amputated, would write the book Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, which would be published in 1943 and made into a movie starring Spencer Tracy, Van Johnson, and Robert Mitchum.

The Doolittle Raiders began holding annual reunions after the war. Their last was held in 2013. Air Force Lt. Col Dick Cole (Ret.), Doolittle’s co-pilot, was the last surviving raider, passing away in 2019.

Additional Sources used in writing this post on the Doolittle Raid

Target Tokyo: Jimmy Doolittle And The Raid That Avenged Pearl Harbor