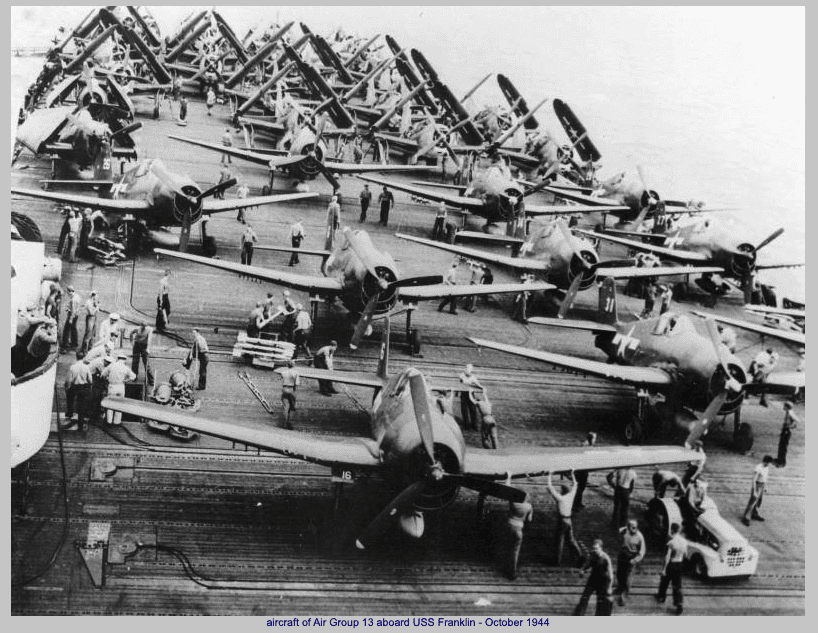

Kamikazes Attack USS Franklin (CV-13)

Normally, 17-year-old Seaman 1/c Walter Gallagher loaded bombs or depth charges into S2BC dive bombers on USS Franklin. But on the afternoon of 30 October 1944, he was helping man a 20mm gun mount on USS Franklin’s port side as the ship’s task group came under attack. Six Japanese aircraft were detected 75 miles out but the Combat Air Patrol was unable to find them. Three peeled away after another target, but the other three, which were kamikazes, bored in on Franklin. Gallagher was on the opposite side of the ship when the first was shot down. It crashed into the sea 20 feet from the starboard side amidships. Both the plane and its bomb exploded on impact with the water, shaking the carrier from bow to stern.1

Right behind it came another, this one a Zeke (Allied code name for the Japanese A6M Zero fighter). It carried a bomb estimated to be 550 pounds. Ensign Bob Slingerland, a VF-13 Hellcat pilot was about to take off when one of the deck crew signaled him to cut his engine, then pointed to the sky. He looked up, saw the attackers, cut his engine, and jumped out of his plane. Slingerland dashed toward the island only to find the hatch closed and dogged. Throwing himself down on the deck he looked up and saw the Zeke appearing to be aiming right at him. He watched it slice through part of his airplane as it crashed into the deck aft of the island. Gallagher, at the gun mount, watched it hit about 40 feet from his position. Fortunately, neither was hurt, but the impact killed approximately 20 men.

“You’re hittin’ him, Lou! You’re hittin’ him!”

The third Japanese pilot, saw that his fellow pilot had struck Franklin. He pulled out of his suicide dive, but attempted to drop his bomb on the ship. It missed, exploding 30 feet off the starboard beam causing no damage. Seaman 1/c Lou Casserino was a 20-mm gunner on the starboard side, forward of the 5-inch turrets. He saw the third pilot level off and fly parallel to the flight deck. As recounted in Joseph Springer’s book, Inferno: The Epic Story of the Life and Death Struggle of the USS Franklin in World War II, he said

He was so close I could see the pilot very clearly. He looked directly at us. He had a Vandyke, the Japanese scarf around his forehead, and he was laughing. My loader had just reloaded my gun so I had a full magazine. I thought I would never get another chance like this. I squeezed the trigger and fired about fifty rounds point blank. I couldn’t use the Mark-14 sight because he was too close. So instead I just used my tracers and watched them blowing off sections of his tail and fueselage. I really hammered him and it was just crazy. My loader yelled,”You’re hittin’ him, Lou! You’re hittin’ him!” I hollered, “Yeah, I know! But he’s not going down!” He was really burning, burning like hell and flying just above the waves. You could tell he was really fighting the controls to stay in the air, and for a second I thought he was going to crash into the waves but he managed to keep going. Then he rose up a little and flopped onto the back of the Belleau Wood.2

Welcome to the third in a three-part series on the actions of USS Franklin in October 1944. Part One is 10-15 October 1944: USS Franklin Attacks. Part Two is The Battles Continue: USS Franklin 15-29 October 1944.

Why Kamikazes?

By the time the US invaded the Philippines in October 1944, the Japanese were reluctantly coming around to the realization that their tactics were not working. Their supply lines had been decimated by US submarines, drastically reducing the flow of fuel and supplies. Many of their most experienced aviators, ships, and ships’ crews had been lost to the attrition warfare of Admiral Chester Nimitz and General Douglas MacArthur.

However, the Japanese had been able to fly hundreds of planes into the Philippines threatening the US’ air superiority. The problem was the majority of the pilots were inexperienced. It took training to plant a bomb on a ship and those pilots didn’t have the time or the fuel to learn. From the lower ranks spread the idea that it was better to die a glorious death in the sky by crashing into a US ship than an ignominious one on the ground by being bombed or strafed.

Superior officers initially resisted the idea, but events soon overtook their conventional wisdom. Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi, who would soon command land-based air assets in the Philippines, began to create a plan calling for Special Attack Squadrons.3

Onishi believed it would take eight bombers with an escort of 16 fighters to sink one carrier where one to three Kamikazes could accomplish the same mission.efn_note]Clark G. Reynolds, The Fast Carriers The Forging of an Air Navy, (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2013) 331[/efn_note]

Franklin had been the victim of one such attempted attack on 15 October. But it had not been approved by the Japanese Command. The pilot’s decision was either a desperate last-minute decision or an act of defiance toward his superiors.

The first successful – and much publicized – sortie occurred on 25 October 1944 when Lt Yukio Seki of the 201 Kokutai led five Zero fighters on a one-way flight. The formation managed to sink the escort carrier St Lo and damaged three others. The theory of ‘one aircraft, one carrier’ was now proven. Word quickly spread and Kamikaze operations took on increased significance. Men volunteered in droves for the so-called ‘Special Attack Corps’. Those who perished would receive a posthumous double rank promotion.4

“Raging Fires Started Instantly Among Planes on the Flight and Hangar Decks” —USS Franklin CV-13 War Damage Report

Back on Franklin, the kamikaze and its bomb penetrated the flight deck. They exploded at about the gallery level in the hangar deck. The plane created a hole in the flight deck about 12 feet by 35 feet. Gallery deck spaces were wrecked, fragments holed aircraft and fuel tanks, and the after-elevator was rendered inoperable. The elevator’s platform itself was forced up two feet and canted at an angle.

On the flight deck, the fires spread to airplanes on the aft end and engulfed the after 5-inch mounts. However, the men were well trained in damage control and fire fighting. Fire hose crews sprang into action. In the hangar, the sprinkler systems were turned on and water curtains in three of the five bays were deployed. At the same time, dense smoke reduced visibility to near zero and it was impossible to fight the fires without rescue breathers5

The initial explosion knocked the radars offline and shut down the Combat Information Center (CIC). Eight aircraft were jettisoned over the side before flames could reach them. Electricians went to work clearing faults and repairing circuits.

Twenty minutes after the kamikaze crashed into the ship, an explosion of gasoline vapors shook the ship. It was strong enough to warp bulkheads and killed many men by concussion alone. Machinist Mate 1/c Joseph Esslinger had gone back into the machine shop to help his friends. He was killed along with Musician Drew Widener and Shipfitter 1/c Robert Orr. Orr had been the first crewman to receive a commendation from the captain during the ship’s shakedown cruise.

Others, like Lt. (jg) Thomas McIntyre, soft-spoken dentist of Minneapolis, with his parmacist’s mates and stretcher bearers, had died at their battle stations, directly in the path of the kamikaze. Scores were painfully burned; many dangerously wounded.6

Within 45 minutes, the fires were under control but not completely out. The ship took on a list of 3 degrees to starboard as the weight of water used for firefighting flowed down through the decks. The crew would work through the night to pump water out of flooded compartments. They freed hundreds of men, some trapped for more than five hours. Slowly, the ship returned to an even keel. Admiral Ralph Davison transferred his flag to Enterprise.

Fifty-six men died in the attack. Sixty were wounded.

The next day, she departed for Ulithi. Upon arrival there, she passed USS Wasp, a sister Essex-class carrier. Its crew gave Franklin three cheers.*

Ensign Slingerland, Seaman 1/c Gallagher, and Seaman 1/c Casserino would all survive the kamikaze attack. Slingerland would leave the ship for another assignment when it reached the dockyard in Bremerton, Washington. Gallagher and Casserino would receive 30 days’ leave and report back to Big Ben. They would both survive the March 19 attack.

Captain James Shoemaker, would receive a Silver Star for his actions on 25 October at the Battle off Cape Engaño. He would be relieved at Ulithi by Captain Leslie Gehres. Shoemaker received a shore assignment and would retire as a rear admiral after the war. When he died, his ashes were spread at sea.

Big Ben was too damaged to be repaired at Pearl Harbor. She was sent to the Bremerton dockyards for repair arriving in late November. USS Franklin was out of the war until March 1945.

*Within minutes of the 19 March attack on USS Franklin, USS Wasp was also attacked by a Japanese bomber. It dropped one bomb killing two hundred men.

Did you arrive here via a search engine? I am the author of the forthcoming book, Heroes By The Hundreds: The Story of the USS Franklin (CV-13). In addition to writing about the bravery of the crews that saved her, I will be writing about the lessons we can learn in leadership and crisis management. I’ll also write about the changes the US Navy made as a result of those lessons learned.

I send out a monthly newsletter, Glenn’s After-Action Report, writing about subjects I find interesting in my research. You can sign up for it below. Feel free to leave a comment or ask a question. Thanks for reading.-Glenn

Footnotes

- Interview With Mr. Walter Gallagher, July 21, 2022, Nimitz Education and Research Center, https://digitalarchive.pacificwarmuseum.org/digital/collection/p16769coll1/id/12842/rec/1 Accessed 26 October 2023

- Joseph A. Springer, Inferno: The Epic Life and Death Struggle of the USS Franklin in World War II, (Minneapolis, MN, Zenith Press, 2011) 154-157

- Rod MacDonald, Task Force 58: the US Navy’s Fast Carrier Strike Force that Won The War In The Pacific (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2021) 355

- Henry Sakaida and Koji Takaki, Genda’s Blade: Japan’s Squadron of Aces: 343 Kokutai, (Hershey, UK: Classic 2003) 69

- USS Franklin CV-13 War Damage Report, US Navy sections 3-6 to 3-11

- Big Ben: The Flat Top: The Story of the U.S.S. Franklin (Atlanta: Albert Love Enterprise, 1946

2 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] in March 1945. Franklin was also involved during the October 1944 Battle of Leyte Gulf and was one of the CVs referred to in the statistics. It also helps me to understand the Navy’s actions during […]

[…] I received an email from the brother of a crew member killed during the 30 October 1944 Kamikaze attack on USS Franklin. He had always wanted to know the latitude and longitude of the ship when his […]