The Battles Continue: USS Franklin 15-29 October 1944

This is the second in a three-part series on Big Ben’s activities that month. (Here is Part 1: 10-15 October 1944: USS Franklin Attacks.)

A personal note: This series of posts focuses on the events of October 1944. Underlying these events was the fatigue experienced by aircrews and ships’ crews. Many of the crews in the Third Fleet had been on duty for months, including Big Ben’s crew which had arrived in the Pacific Theater (PTO) in July. From 10 October to 30 October 1944, the ship’s crew and the officers and men of Air Group 13 aboard USS Franklin spent 18 days in combat, including a stretch of 12 straight days.1 Fatigue in the fleet was a major concern of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Admiral Nimitz. Wheels were in motion to address shortages of officers and men at all positions, but it would be months before they would be eased.

As you read about these events, think about the workload, the stress, and the fear the overworked ship’s crew and the men of Air Group 13 faced. Also, the courage they displayed. Pause and think about the leadership, the teamwork, and the just plain hard work required to fight a ship for 18 of 20 days in an active combat zone.

Think of the hundreds of sorties flown off the deck. Many aircrews often flying multiple sorties a day. As each plane returned from a sortie, it had to be refueled, rearmed, or repaired. These required armorers to arm, plane captains to direct and position aircraft, and mechanics to repair. Not only did those on the flight deck have to be concerned with danger from the Japanese, but they also had to cope with dangerous propellors, the occasional crashing plane, negligent discharges from machine guns, and other dangers.

At the same time, the ship’s crew had to drive the ship keeping the boilers, engines, catapults, arresting gear, radar, radios, and other critical components working. They had to be fed, doctored, and ministered to. The anti-aircraft batteries had to be at optimal effectiveness. And there was little rest for the weary. They were often called to General Quarters to man their battle stations when they tried to eat or grab some sleep.

The average temperature in the Philippines in October is 85 degrees Fahrenheit. Only the aircrews’ ready rooms were airconditioned. Conditions in the other parts of the ship, especially the engine and boiler rooms were often above 100 degrees. Many of the sleeping berths were directly under the flight deck and were often noisy. And many worked in cramped and uncomfortable compartments. That did not stop them from doing their duty.

Finally, this series of posts focuses on the actions of Franklin. Space prevents the vigorous discussions around the choice of invading the Philippines over Formosa. As well, this post doesn’t mention the controversy over Halsey’s decisions during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Now let’s turn the clock back…

By October 1944, the US Navy had rolled back Japanese bases in the Central Pacific. Meanwhile, General Douglas MacArthur’s troops had done the same driving northwest along and on islands near the New Guinea coast. Admiral Nimitz originally favored an invasion of Formosa (today called Taiwan). At the same time, MacArthur wanted to make good on his promise to return to the Philippines. Nimitz came to realize that Formosa would require too many resources and the decision was made by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to invade the Philippines. The Philippines were needed to provide land-based airfields and logistical support in the attack on the remaining Japanese possessions and its home islands.2

15 October 1944

On 15 October, USS Franklin’s Air Group 13, part of TG 38.4* was busy destroying Japanese airplanes and airfields on Luzon. Meanwhile, her Combat Air Patrols and her anti-aircraft crews defended her against numerous attacks from the air. As mentioned in Part 1, her fighters shot down 29 aircraft and her anti-aircraft crews accounted for another that day. But the Japanese were able to land a blow of their own. Three Japanese airplanes made it past the Combat Air Patrol (CAP). One dropped a bomb which slightly damaged the deck-edge elevator (#2). One source reported three killed and 12 wounded, another 8 killed and 27 wounded. The bomb’s shrapnel shredded airplane gas tanks starting a small gasoline fire in the hangar.3 Air attacks continued through the afternoon but none reached Big Ben again that day.

16-22 October 1944

On the 16th heavy air strikes were launched against the Manila Bay area with emphasis on shipping. At the day’s end, hulks of half-sunken ships dotted the shallow water of Manila Harbor, and clouds of smoke poured from the stricken shore installations.

While the aircraft carriers pounded the Japanese bases in the Philippines and the tempo increased to the fury of preinvasion assault, the mighty fleet of transports, battleships, escort carriers, and all the SEVENTH Fleet drew near Leyte. On 21 October 1944, the troops of the Sixth Army poured ashore on Leyte; the reinvasion of the Philippines had commenced. –History of USS Franklin CV-13

Battle of Leyte Gulf

When the Japanese lost Saipan in July, the Japanese changed their strategy, focusing on a decisive battle in either the Philippines, Formosa, or two areas in Japan. They believed they had no choice as they realized that the loss of the Philippines would result in the severing of Japan’s supply lines to the East Indies. Once they realized the US was invading the Philippines, they started their fleet in motion.4 (For the battle’s bigger picture, I recommend The Battle of Leyte Gulf 23-26 October 1944, by Thomas J. Cutler. It’s a very readable one-volume book.)

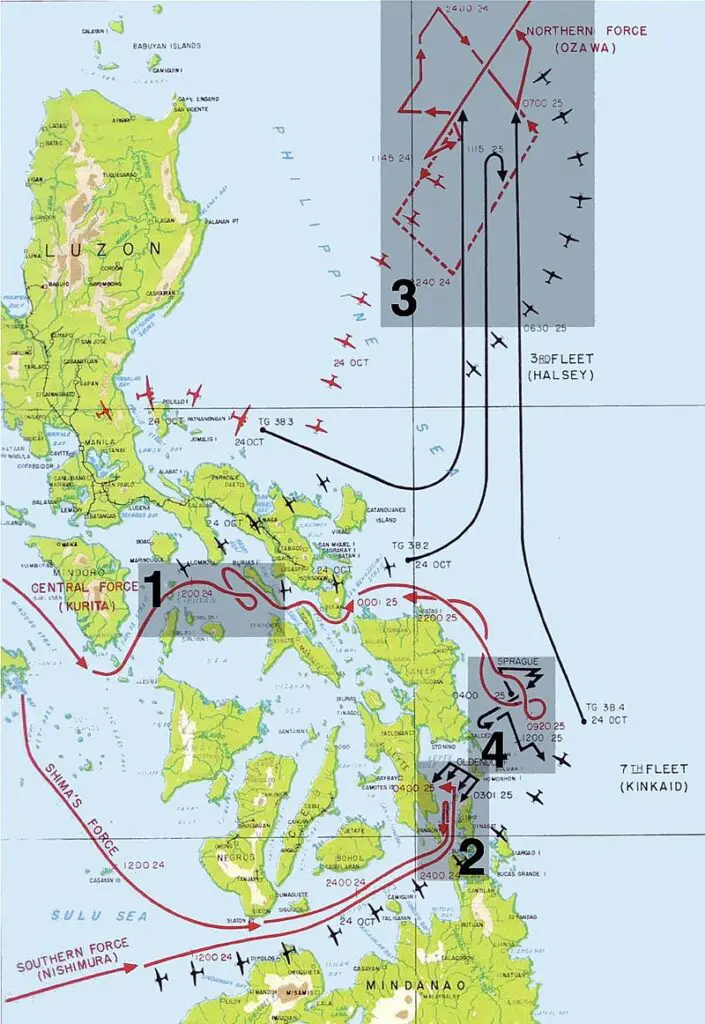

On the evening of 23 October, Admiral William Halsey, commanding THIRD Fleet, received word that the Japanese fleet was on the move, approaching his positions. TG 38.4 was recalled and ordered back as Halsey consolidated his forces.**

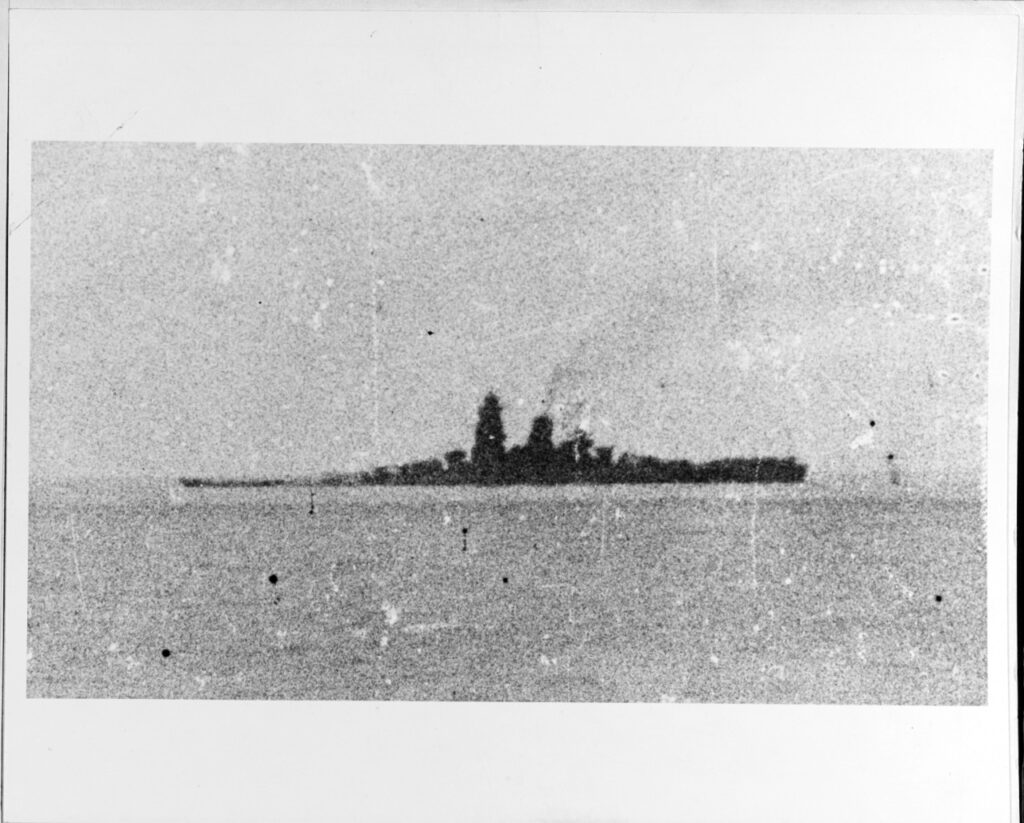

On the morning of 24 October, scouts from another carrier sighted Admiral Kurita’s “Center Force.” Composed of five battleships, nine cruisers, and thirteen destroyers, it became a magnet for attacking US aircraft. Two of the battleships, Yamato and Musashi, were the most powerful ever built with 18.1-inch guns.

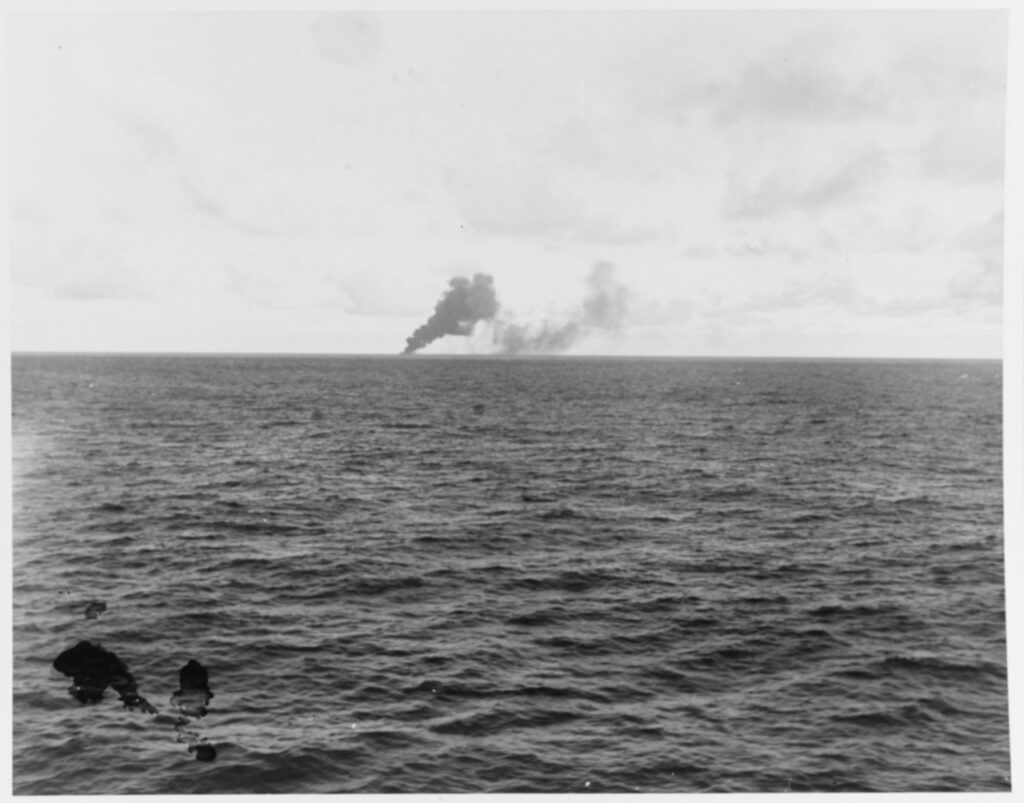

In the Sibuyan Sea, 65 planes from Franklin and Enterprise attacked Admiral Kurita’s force, focusing on Musashi and Yamato. Musashi received most of the punishment. Yamato suffered slight damage. It would play a role later in the day attacking the jeep carriers of Taffy 3. Aircraft from Cabot, Essex, and Intrepid joined Big Ben and Enterprise on the attack causing Musashi major damage. She lost speed and fell out of formation eventually sinking hours later.5

During the attack on Kurita’s force, Lieutenant (j.g.) Irving Fellner led a section of bombers from VB-13 and would be awarded the Navy Cross. His citation read:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Lieutenant [then Lieutenant, Junior Grade] Irving Stanislaus Fellner, United States Naval Reserve, for extraordinary heroism in operations against the enemy while serving as Pilot of a carrier-based Navy Scout Dive Bomber in Bombing Squadron THIRTEEN (VB-13), attached to the U.S.S. FRANKLIN (CV-13), in action against enemy Japanese forces during the Battle for Leyte Gulf, on 24 October 1944. Participating in a vigorous strike against a large enemy Task Force in the Sibuyan Sea, Lieutenant Fellner boldly led his section in the face of intense and continuous hostile anti-aircraft fire and skillfully maneuvered his plane to score a direct hit upon a Japanese battleship, crippling it severely. By his brilliant airmanship, daring initiative and gallant fighting spirit, maintained against tremendous odds, Lieutenant Fellner contributed materially to the overwhelming damage inflicted upon the Japanese Fleet during this historic battle. His outstanding courage and inspiring leadership reflect the highest credit upon himself and the United States Naval Service.6

It is unknown which battleship he attacked, but it is likely it was Musashi. Yamato was not “crippled severely.” Fellner had just celebrated his 23rd birthday three days earlier.

Battle off Cape Engaño

But the day wasn’t over yet. Admiral Halsey had been looking for the Japanese carriers (who were being used as decoys to pull him away from protecting the landing forces). Scout planes found them to the north.

Halsey ordered Admiral Ralph Davison, commanding Franklin’s task group, to speed north to join him. They did so, and now Halsey had three of his four task groups (the fourth was being refueled). At 6:30 a.m. on October 25, the US carriers launched strikes that found the Japanese carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. Aircraft from Franklin and Lexington (CV-16) struck the carrier Chiyoda. She was “set heavily afire, causing flooding and a sharp list.“7

Other aircraft from Franklin attacked a destroyer and two cruisers defending her. Air Group 13 also joined other carriers in attacking the carrier Zuiho, which would later sink from the damage.8 Halsey’s carriers were then ordered south as Admiral Kurita’s battleship force had returned and attacked Taffy 3. It was composed of Jeep carriers, destroyers, and destroyer escorts providing ground support to the American army. Taffy 3 was not prepared to face battleships. Fortunately, a determined stand by its ships and aircrews turned Kurita away after sinking USS Gambier Bay, an escort carrier. (A more complete recounting can be found by reading The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors, by James Hornfischer. I highly recommend it.)

26-29 October 1944

On 26 October, Big Ben moved away from the combat zone to refuel and replenish her munitions and other supplies. On the 27th she returned to Leyte, flying air cover for the transports and searching for fleeing Japanese ships. Six fighter-bombers from VF-13 found and attacked a cruiser and two destroyers south of Mindoro. They bombed and rocketed the cruiser which sank after they returned to Big Ben. The two destroyers were also damaged.9

28 and 29 October saw Big Ben again flying ground support for the Army. She also flew combat air patrol for the fleet and its transports. The next day, 30 October, would see Franklin’s greatest trial to date. Part 3 of this series will discuss those events.

*There were four task groups in Task Force 38. Task Group 38.4 was commanded by Admiral Ralph Davison who flew his flag from Franklin. Other carriers in the task group were USS Enterprise, CV-6, USS San Jacinto, CVL-30, and USS Belleau Wood, CVL-24. Enterprise was a Yorktown-class carrier and the most storied carrier of World War II. San Jacinto and Belleau Wood were light carriers, smaller than Franklin and her Essex-class sisters. Positioned around these carriers to provide air, surface, and submarine defense were battleships, cruisers, and destroyers.

**On 23 October, the American fleets were under near-continuous attacks from Japanese land-based aircraft. Near the landing beaches, one survived the American air and ship-based defenses dropping a bomb on the USS Princeton, CVL-23, a light carrier. The cruiser, USS Birmingham, CL-62 came alongside to render assistance. During the rescue attempt, there was a massive explosion onboard Princeton showering Birmingham with shrapnel-like fragments and debris. 229 men of Birmingham would be killed in that explosion. This is why, months later, when USS Santa Fe came to the aid of Franklin on 19 March 1945, Captain Harold Fitz of Santa Fe asked Captain Gehres if his magazines had been flooded. Captain Fitz did not want the same thing to happen to his ship that happened to Birmingham.

Did you arrive here via a search engine? I am the author of the forthcoming book, Heroes By The Hundreds: The Story of the USS Franklin (CV-13). In addition to writing about the bravery of the crews that saved her, I will be writing about the lessons we can learn in leadership and crisis management. I’ll also write about the changes the US Navy made as a result of those lessons learned.

I send out a monthly newsletter, Glenn’s After-Action Report, writing about subjects I find interesting in my research. You can sign up for it below. Feel free to leave a comment or ask a question. Thanks for reading.-Glenn

Footnotes

- Office of Naval Records and History, Ship’s Histories Branch, US Navy, History of USS Franklin CV-13, USS Franklin (CV-13) Original Documents 1943-1946 (Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 1994) 76-77, 84-87

- Clark G. Reynolds, The Fast Carriers The Forging of an Air Navy, (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2013) 243-246

- Steve Jackson, Lucky Lady: The World War II Heroics Of The USS Santa Fe and Franklin (New York: Carroll and Graf, 2004) 209-210 and Joseph A. Springer, Inferno: The Epic Life and Death Struggle of the USS Franklin in World War II, (Minneapolis, MN, Zenith Press, 2011) 120

- Trent Hone, Mastering The Art of Command: Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and Victory in the Pacific (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2022) 359, 387

- Thomas J. Cutler, The Battle of Leyte Gulf, 23-26 October 1944 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2001) 148-153

- Irving Stanislaus Fellner, AWARDED FOR ACTIONS: Navy Cross, https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/19129, accessed 19 October 2023

- Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States naval operations in World War II. Vol XII (Castle Books: Edison NJ, 2001) 325

- Office of Naval Records and History, Ship’s Histories Branch, US Navy, History of USS Franklin CV-13, 85

- Office of Naval Records and History, Ship’s Histories Branch, US Navy, History of USS Franklin CV-13, 85