USS Franklin Arrives Pearl Harbor 3 April 1945

Bloody and battered, USS Franklin arrived in Pearl Harbor on 3 April 1945, the victim of a devastating conflagration caused by a single Japanese bomber’s attack 16 days earlier. The US Navy would later announce that 807 men died in the attack. Only USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor and USS Indianapolis, later in 1945, saw more men die on one ship.

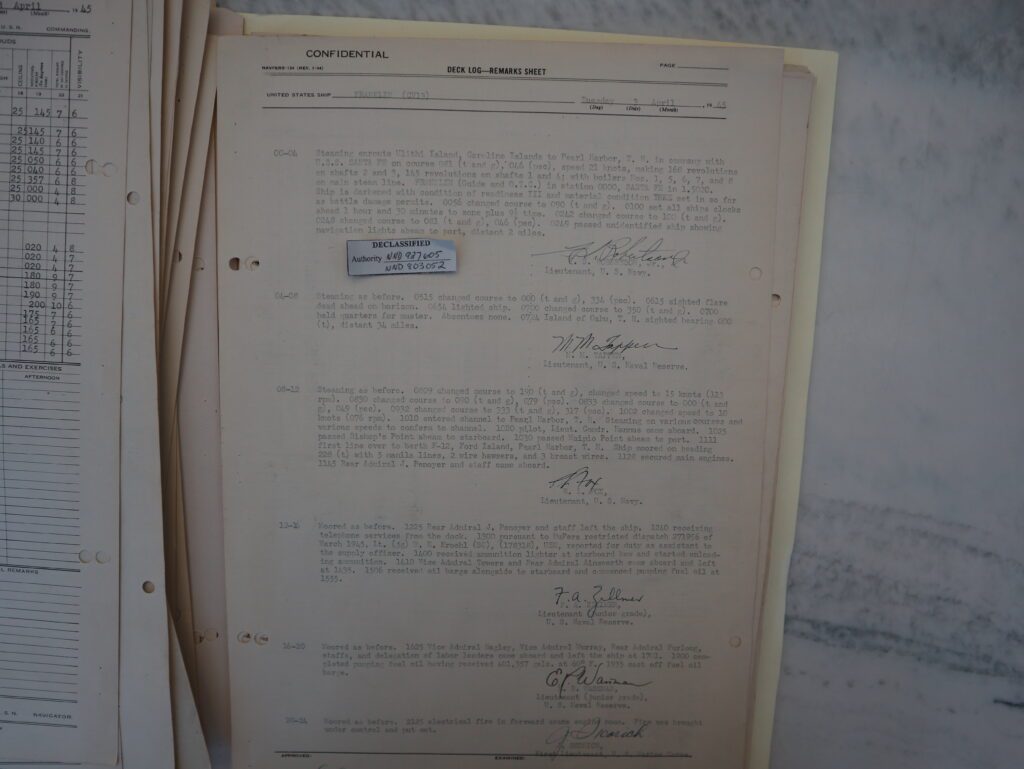

The crew’s heroic efforts preceded her, and there was quite a welcoming committee dockside when she arrived. In Lucky Lady: The World War II Heroics of The USS Santa Fe and Franklin, author Steve Jackson wrote that 50 women of the Navy’s Women’s Reserves (WAVES) started to sing, America The Beautiful, as the ship approached the dock[1]. Also waiting, according to the ship’s deck log for that day, was Rear Admiral J. Penoyer and his staff.[2]

Everything went smoothly until it became apparent that Franklin was approaching the dock too fast. Everyone assembled on the dock scrambled for safety as the ship smacked the dock. Captain Leslie Gehres ignored the practice of using a harbor pilot when entering and leaving Pearl Harbor, insisting on conning the ship himself. On that day, the pilot was Lt. Cmdr. M. Hannus, who had conned the ship, as well as other carriers, many times before.[3] But Gehres refused his help.

Captain Gehres blamed the mooring crew for the incident.

In his oral history, Stephen Jurika, the ship’s navigator, mentioned that Gehres “…would have no pilot, no way…He was at the conn every time we entered or left.”[4]

Jurika went out of his way on another occasion, the ship’s arrival in Ulithi on 13 March 1945, to complement Gehres on his ship handling after steering the ship to its berth. “I don’t think he was more than 25 yards out of position.”[5]

The Deck Logs Differ

However, the ship’s deck logs tell a different story. I could find no mention of a pilot when the ship arrived at Bremerton in November 1944. The deck log did mention a pilot when the ship left on 31 January 1945. The ship does not specify who had the conn.

On 4 February 1945, as the ship sailed underneath the Golden Gate Bridge, the deck log reported that the pilot, Mr. Rode, assumed the conn. (It is unknown if he had the conn for the entire time, though.)

Other departures and arrivals from Pearl Harbor on 13 February 1945, 16 February, 20 February, 23 February, and 3 March all mention that a pilot had the conn. (Franklin was training its aircrews in the waters around Pearl Harbor during February as the ship readied for its Operational Readiness Inspection (ORI).

I have read elsewhere that it was standard practice for ships entering and leaving Pearl Harbor to use a pilot to navigate the narrow and shallow waters.

When there is an apparent conflict between two sources, as we have between Captain Jurika and the deck logs, it becomes more difficult to discern what happened. In this case, the deck logs are more accurate. In fairness to Captain Jurika, his interview was conducted 24 years after the attack. (By the way, the 3 April deck log does not mention who had the conn, and Jurika omits mentioning the ship smacking the dock when she arrived.)

Jurika was right that Gehres was an exceptional ship handler. He had spent his early career in destroyers, commanding three of them before he went into aviation. However, the deck logs do not specify if one of the officers relieved the pilot at any point during the trips where one was onboard.

As the deck logs show, harbor pilots were onboard Franklin as it entered or left various ports. We will likely never know why he refused to use a pilot on 3 April. Perhaps he had overworked himself in the two weeks since the attack, suffered fatigue, and misjudged his approach. Or maybe his pride kept him at the conn. This is one of the mysteries of Franklin’s story that fascinates me.

I will continue researching this.

Did you arrive here via a search engine? I am the author of the forthcoming book, Heroes By The Hundreds: The Story of the USS Franklin (CV-13). In addition to writing about the bravery of the crews that saved her, I will discuss the lessons we can learn in leadership and decision-making and the changes the US Navy made because of those lessons.

Feel free to follow me on Facebook. There, I am M. Glenn Ross, Author. I also write a monthly newsletter, Glenn’s After-Action Report, about subjects I find interesting in my research. You can sign up for it below. Feel free to leave a comment or ask a question. Thanks for reading.

-Glenn

[1] Steve Jackson, Lucky Lady: The World War II Heroics Of The USS Santa Fe and Franklin (New York: Carroll and Graf, 2004) 449

[2] USS Franklin Deck Log, Tuesday, 3 April 1945 (National Archives, Box 3665 P118-A1)

[3] USS Franklin deck logs for 21 November 1944; 22 November 1944; 20 February 1945; 3 April 1945

[4] Jurika, Capt. Stephen, The Reminiscences of Capt. Stephen Jurika, Jr., USN (Ret.), Vol. II, Interview by John T. Mason, Jr . 1979, US Naval Institute: Annapolis 608

[5] Jurika, 619