US Cruiser Captains Courageous

Author’s Note: This post originally used the phrase “deliberately sideswiped” to describe Captain Harold Fitz’s actions on his second approach to Franklin. A retired US Navy captain pointed out to me that my characterization was incorrect. Below is the more accurate revised version. I apologize for the error. – Glenn

One of the stories I find fascinating about the attack on USS Franklin on 19 March 1945 is the action taken by Captain Harold Fitz, USN. He commanded the light cruiser USS Santa Fe (CL-60). Franklin and Santa Fe were part of Task Group 58.2, one of four task groups comprising Task Force 58. With more than 100 ships and 100,000 men, the task force was off the coast of southern Japan on a mission to destroy as many Japanese air and naval assets as possible before the invasion of Okinawa, 11 days away.

At 0708 that morning, while launching aircraft, a lone Japanese bomber snuck through the task force’s defenses, dropping two bombs on Franklin. At that moment, there were 31 aircraft on the flight deck and 22 in the hangar. Many of those on the flight deck were fully armed and fueled. Those on the hangar deck were in various stages of being readied for a mission. Eleven of the aircraft on the hangar deck had full belly tanks and were armed with 11.75-inch Tiny Tim rockets. 1 Each packed enough explosives to sink a destroyer, merchant ship, or cruiser. The two bombs caused one of the largest conflagrations ever to erupt on any ship. There were numerous secondary explosions, and hundreds of the crew were killed outright.

Santa Fe was one of two cruisers sent to aid Franklin. Captain Fitz twice brought his ship alongside Big Ben, as her crew called her. Her war diary stated:

Previous experience [the first approach] had shown that we could not maintain position clear of the Franklin, or from such a position effectively fight the fires or rapidly transfer personnel, and it was decided to place the ship alongside, accepting the damage to the ship by the radio masts, gun sponsons and other projections from the hull of the FRANKLIN.2

To me, the above entry is a masterfully written understatement. In his book, Lucky Lady: The World War II Heroics of the USS Santa Fe and Franklin. author Steve Jackson wrote that the decision was the captain’s alone and that the helmsman was so dumbfounded that Fitz had to order him twice to turn the ship onto what the helmsman considered a collision course. But Fitz skillfully steered the cruiser right up next to Franklin “as though Fitz was parallel parking a car between two other vehicles.”3

With the two ships locked together, approximately 800 men transferred from the stricken carrier to Santa Fe. The Santa Fe crew also played a significant role in fighting the fires onboard Franklin.4

Ever since I first read about Captain Fitz’s actions, I’ve wondered where he came up with the idea of coming up close alongside a burning carrier to render aid.

Bringing a ship alongside another while in battle can be dangerous. At the Battle of Midway, the destroyer USS Hammann (DD 412) was moored to the damaged USS Yorktown (CV-5), transferring men and providing power. The Japanese submarine, I-168, penetrated the destroyer screen and fired four Type 94 torpedoes from 1200 yards. Hammann was cut in half by one of the torpedoes. Two others struck Yorktown, administering her coup de grâce.5

Cruiser USS Birmingham Aids USS Princeton

Catalog #: 80-G-287970

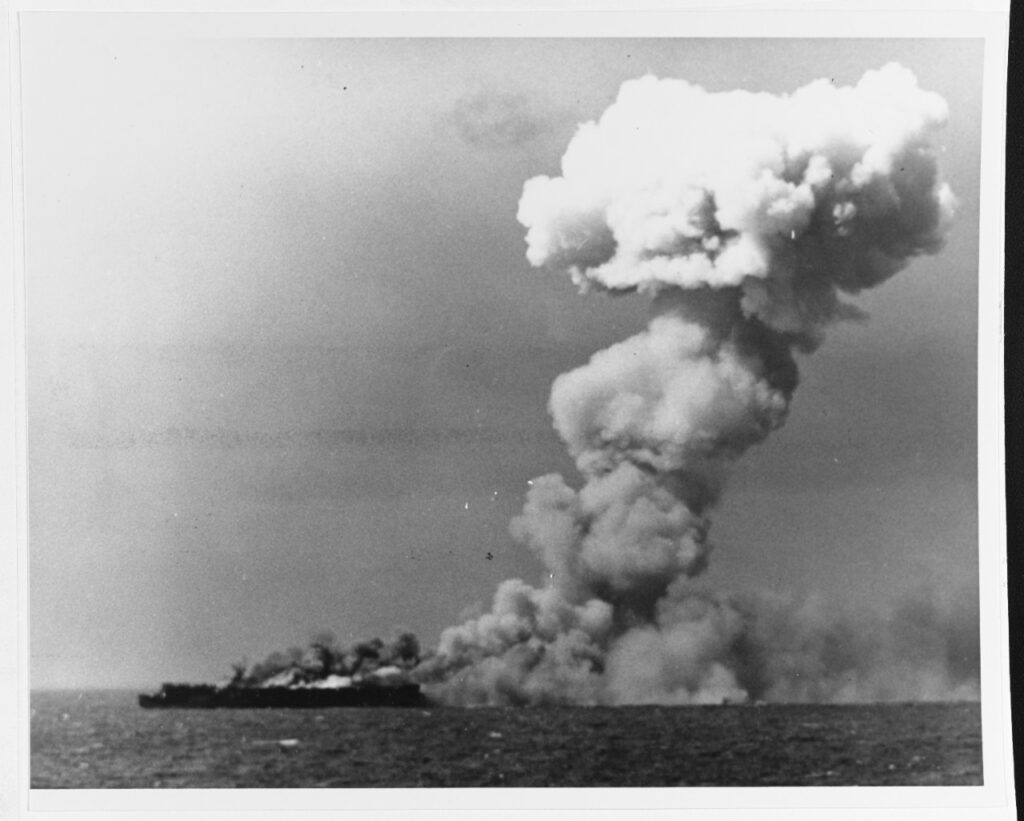

While Captain Fitz may have been the first to moor a cruiser to a burning fleet carrier, he most likely got the idea of rendering close aid from the USS Birmingham, one of Santa Fe’s sister ships. On 24 October 1944, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, USS Princeton, CVL-23, a light carrier, was assigned to Task Group 38.3. That day, the group fought off three waves of Japanese aircraft, each containing 50-60 attackers, with the combat air patrols shooting down the majority and anti-aircraft accounting for more. Still, a lone Japanese bomber, using the same tactics as the one attacking Franklin five months later, snuck through the task group’s defenses. Attacking from aft, it dropped a single 550-pound bomb that penetrated through the hangar and flight decks, exploding in Princeton’s bakery. Six TBF Avengers on the hangar deck were loaded with torpedoes, which detonated in a chain reaction, blowing one elevator as high as the ship’s mast and sending another crashing onto the flight deck.

Escorting destroyers came to her aid, and the cruiser USS Birmingham (CL-62), Captain Thomas Inglis in command, arrived soon after. Inglis became the Officer in Tactical Command (OTC) of the rescue. He ordered another cruiser, USS Reno (CL-96), to provide anti-aircraft defense while he took his ship up alongside Princeton. At 1100, Birmingham began passing fire hoses to firefighters aboard the carrier. Ultimately, Birmingham would send 14 streams of water into Princeton, helping to extinguish fires in the forward part of the ship.

However, several bogies were identified as inbound, and one of the destroyers reported a possible sonar contact, which could have been a Japanese submarine. Birmingham’s Action Report stated:

Accordingly at 1330, after 2 1/2 hours of almost uninterrupted work, all but two men of fire-fighting party were hastily returned and Birmingham with great reluctance discontinued fire-fighting operations.6

At 1455, Birmingham again approached Princeton. The dangers from the air attack had dissipated, and the sonar contact was believed to be false. The damage control parties had reported that fires were now confined to the aft portion of the ship and that prospects for extinguishing them were “very good.”7

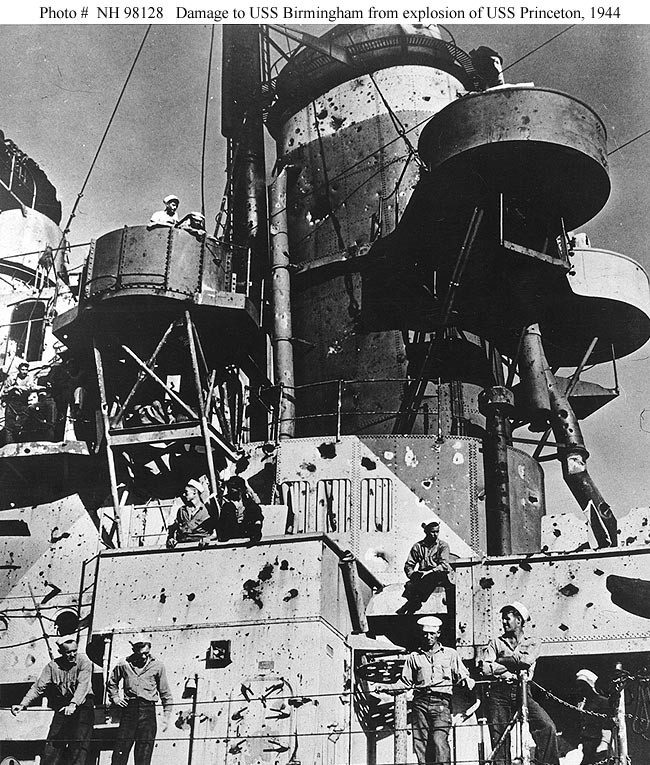

Catastrophe struck at 1523! A tremendous explosion from the “after portion of the Princeton” blew the stern off the carrier. Birmingham was angled at 30 degrees about 50 feet away, amidships of Princeton. The cruiser’s decks were full of men deploying fire hoses, pulling men out of the water, and rendering medical assistance. The explosion showered the cruiser with large and small debris, killing 229 of its crew, with four missing in action. Another 211 were severely wounded, with 215 receiving wounds “minor to severe.” Both the captain and the Officer of the Deck (OOD) were incapacitated. Wounded, but not severely, the ship’s Executive Officer took command. 8 With over half of her crew wounded or dead, Birmingham was out of the war and had to return to the United States. Captain Inglis would receive the Navy Cross for his actions that day.

Cruiser Santa Fe Assists USS Franklin

Five months later, in March 1945, Captain Fitz of Santa Fe found himself in a similar situation as he approached the damaged USS Franklin. Remembering what had happened to Birmingham, he messaged Franklin, “Are your magazines flooded?” Franklin’s Captain, Leslie Gehres, responded, “Not sure. We think so.” 9

Although hoping for a different answer, Captain Fitz brought his ship alongside the burning carrier twice to provide important fire-fighting and evacuate non-essential and wounded crew members. The second time, he came close alongside Franklin. I believe he analyzed the situation and concluded that this was the only way for him to expedite rescuing the wounded and providing firefighting assistance. (I will continue to research this.) He did this believing (wrongly as was discovered later) that Big Ben’s magazines had been flooded.

For his actions that day, Fitz would also receive the Navy Cross.

USS Wilkes-Barre Comes To The Aid of USS Bunker Hill

Catalog #: 80-G-K-5274

Not quite two months later, on 11 May 1945, during the Battle of Okinawa, USS Bunker Hill (CV17), a sister ship of Franklin, would be struck by two kamikazes. One of the ships that came to her rescue was the cruiser USS Wilkes-Barre (CL-103). Her captain, Robert L Porter, brought his ship close alongside Bunker Hill as Captain Fitz of Santa Fe had done. Her action report recorded:

1115 – Came close alongside BUNKER HILL whose overhanging 40 milimeter[sic] gun sponsons damaged our 40 millimeter mount No. 48, 40 millimeter clipping room No. 44; buckling main deck slightly, port side of forecastle, and carrying away life lines in order to rescue about forty (40) men who were driven by flames and explosions to this ship from the carrier.10

The heroic actions of these three cruiser crews saved more than a thousand lives across these three incidents and may have saved Franklin. Had Princeton’s torpedo magazine not exploded, Birmingham’s crew and the destroyers’ crews that also came to her aid may have saved her, as most of the fires had been extinguished.

After learning about each of these three cruiser captains and how they faced down danger, I am reminded of the phrase, “…the finest traditions of the US Naval Service.” They saw their duty and did it without wavering. If you are here because you are a student of leadership, I urge you to learn more about the actions of these three officers. You’ll find my sources below.

Did you arrive here via a search engine? I am the author of the forthcoming book Heroes By The Hundreds: The Story of the USS Franklin (CV-13). In addition to writing about the bravery of the crews that saved her, I will discuss the lessons we can learn in leadership and decision-making, and the changes the US Navy made because of those lessons.

Feel free to follow me on Facebook. There, I am M. Glenn Ross, Author. I also write a monthly newsletter, Glenn’s Action Report, about subjects I find interesting in my research. You can sign up for it below. Feel free to leave a comment or ask a question. Thanks for reading.

-Glenn

Footnotes

- USS Franklin CV-13 War Damage Report Navy Damage Control Report September 1946, 15

- War Diary of the U.S.S. Santa Fe for the month of March 1945, 15, Accessed via Fold3.com

- Steve Jackson, Lucky Lady: The World War II Heroics Of The USS Santa Fe and Franklin (New York: Carroll and Graf, 2004) 403

- Operations of U.S.S. Franklin during the period from 14 March to 24 March 19045 – Action Report of 4-5

- Craig Symonds, The Battle of Midway (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011) pp 347-350. Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully, Shattered Sword; The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2007) 374

- USS Birmingham Action, Report of, During Fleet Operations 18-24 October 1944 p 9, Accessed via Fold3.com

- USS Birmingham Action Report, 10

- USS Birmingham War Diary, Month of October 1944, 21, Accessed via Fold3.com

- Steve Jackson, Lucky Lady 385

- USS Wilkes-Barre Action Report – Operations from 14 March to 1 June 1945 in support of Commander FIFTH FLEET Operation Plan No. 1-45, 12