March 25th Is National Medal of Honor Day

Today, 25 March, is not just any day; it’s National Medal of Honor Day. This day, as per the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, holds a significant place in our history:

Medal of Honor Day, held annually on March 25, provides an opportunity for Medal of Honor Recipients and the public alike to pause and reflect on the importance of service and sacrifice. National Medal of Honor Day was first observed on March 25, 1991, when Congress declared it as a day to “foster public appreciation and recognition of Medal of Honor Recipients.” The selected date has an important place in Medal of Honor history, as March 25, 1863, was the date of the first Medal of Honor presentation. On that day, Private Jacob Parrott became the first Recipient of the Medal of Honor. Parrott’s was one of six Medals of Honor presented that day to the Andrews Raiders, a group who showed the values of courage, commitment, sacrifice, integrity, commitment, and patriotism, which are still important to Recipients of the Medal of Honor today.

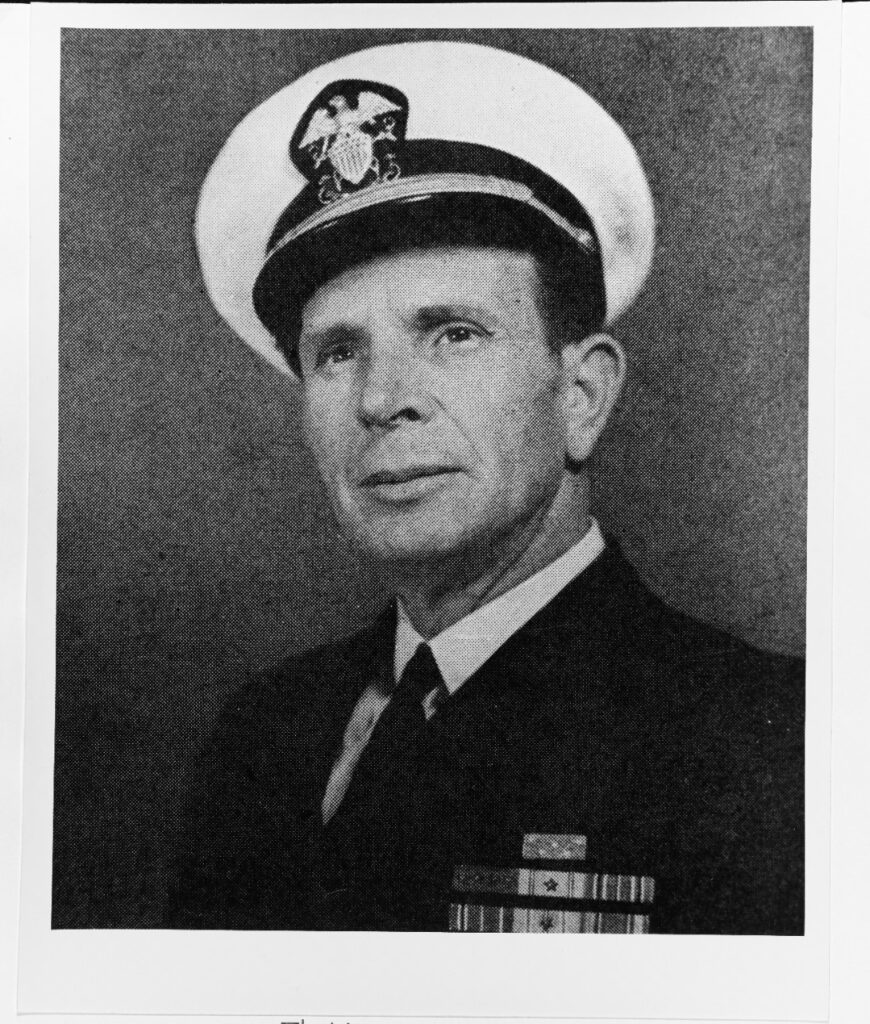

As I learn more about the stories of the crews of USS Franklin and the ships that came to her aid on 19 March 1945, I am confronted with truly awe-inspiring acts of bravery and sacrifice. Lt. Commander Joseph O’Callahan, the first priest or chaplain to receive the Medal of Honor, and Lt. (j.g) Donald Gary, a Mustang who rose through the ranks, would each be presented with the Medal of Honor. We can learn a great deal about courage and leadership from their actions.

“To Say I Wasn’t Scared Would Be Untrue”

Lieutenant Gary is most famous for rescuing 300 men from the crowded messhall. That alone may have earned him a Medal of Honor, but that wasn’t the end of his day. Later, he rescued eight men from the forward machinery spaces who had taken refuge in the bilges, first fighting fires that prevented their escape. Next, he and two men went below into machinery spaces, where the temperature had soared to 130 degrees Fahrenheit, to restart boiler #5. Several hours later, they succeeded and started working on the other boilers.

What We Can Learn From Lt. Gary’s Actions

He was prepared. In an oral history for the book USS Franklin: The Ship That Wouldn’t Die, he wrote that he had spent the last few months familiarizing himself with the ship’s passageways, compartments, and ventilation trunks; he was able to plan an escape route that would lead the 300 men to safety. He and the 300 likely would not have survived if he had not known his ship.

The men in that messhall respected him. Some knew him, and they knew what he could do. Others didn’t, but they saw he wasn’t panicking and that he had a plan.

He didn’t panic. Once he calmed down, he focused on the problem at hand. In that account, he wrote:

To say I wasn’t scared would be untrue and I believe I can say the same for everyone there. I’m of the opinion that in certain emergencies everyone’s reasoning power slows down – everyone’s reaction is different – and the human doesn’t click as it should.

He led from the front. He went himself; he didn’t send anyone to find the escape route from the messhall or rescue those in the machinery spaces. When it came time to see if they could restart the boilers, he led two men down to the machinery spaces.

He didn’t stop; he kept going. After he rescued the men from the mess hall, the ship was still in danger. He fought fires, freed trapped men, and helped restart the boilers. Later, the Navy revised the death toll to 807. Had Lieutenant Gary not rescued those 300-plus men, the death toll would have exceeded 1100. His actions in getting the boilers relit meant that the ship could leave the battle space and reach safety sooner than if it had to rely on a tow for the entire trip back to Ulithi.

…The Mad Clutch For Life

Lieutenant Commander Joseph O’Callahan, the ship’s Catholic chaplain, was new to the ship, having just come on board more than two weeks before. He’d served a tour aboard the USS Ranger, CV-4, earlier in the war.

He was eating breakfast when the first explosion knocked him to the deck, disorienting him. In his memoir, I Was Chaplain On The USS Franklin, he wrote:

Those first moments were given over to instinct, the mad clutch for life. I crouched underneath a table, inconsequentially shielding my head from bits of glass which pelted from broken light fixtures. Hundreds of tons of high explosives ready to blow up, and I shielded my head from bits of glass! But I followed blind instinct only for a split second until my mind focused.

Along with the others in the mess hall, “Father Joe,” as he was known, made his way to the fo’c’sle in the ship’s bow.

When they bottlenecked at a scuttle (a small hatch ) at the top of a ladder, he calmly instructed them to get into a single file, the only way to pass through the opening.

“…I Went In Search Of My Proper Work”

After arriving at the fo’c’sle, he returned to his quarters and retrieved his helmet with the cross, a defective life belt, and his vial of holy oils.

And thus, belted with a defective float, helmeted with the cross, carrying the holy oils for the dying, I went in search of my proper work.

What We Can Learn From Father Joe’s Actions

He acted, not paralyzed by fear. At first, he ministered to the wounded and gave last rites to the dead. No one had to tell him what to do; he knew how to make a difference. Father Joe was claustrophobic, yet when Captain Gehres yelled down from the bridge and asked him to organize a party to remove the shells in the confined spaces of one of the 5-inch turrets, he did so without question.

Later, accompanied by another officer, he braved the smoke and poor visibility of the hangar deck to determine whether they could fight the fires from that deck and the flight deck.

Note that he was not in the chain of command, but he did have authority.

I asked eight men to come with me and help Commander Hale, Lieutenant Harris, and Lieutenant Morgan. Eight men came to the fire lines, then another eight, and another. When one hose crew, choking with smoke, had reached the limit of endurance, another crew would relieve it. The men were not following me as much as they were following the Cross. For better or worse, I had become a symbol. My helmet was far more important than my head.

Let’s recap. He

- Helped lead frightened sailors from below decks to the safety of the fo’c’sle.

- Ministered to the dead and injured.

- Organized firefighting crews.

- Organized and led a chain gang to empty out a magazine in a 5-inch gun turret. (Had that magazine exploded, it would have killed many, if not sinking the ship.)

- Delivered messages from the captain both in person and via the one surviving phone line to those trapped in the engine room.

- Accompanied by another officer, he braved the smoke and dangerously poor visibility of the hangar deck to determine whether they could fight the fires from that deck and the flight deck.

Many other men would also receive recognition; this crew received more decorations than any other in US Navy history. Unfortunately, even Captain Gehres admitted that others deserved recognition but didn’t get it.

The traits they had in common, to me, are:

- Respected by others

- Controlled their fear

- Kept calm

- Thought clearly to solve problems

- Ignored the danger to themselves

- Pitched in where they were needed time and time again

On this National Medal of Honor Day, we should remember their actions and those of the other Medal of Honor recipients. There is much we can learn from them.