How Action Reports Helped The US Navy Defeat The Japanese

Multiple effective feedback mechanisms are crucial for any organization striving to stay competitive in a changing environment. Everyone, from senior management to frontline employees, plays a vital role in this process. Their feedback should be heard, valued, and acted upon, making each person an integral part of the organization’s quest to stay competitive. In this decade alone, organizations have had to respond to the challenges of COVID-19 and the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), to name two. Many are successful because they value feedback from their employees, customers, vendors, and others.

The US Navy Implements Learning Systems To Stay Competitive

Perhaps the ultimate competitive environment is that of warfare. In his book Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine In The US Navy 1898-1945, Trent Hone writes that the US Navy has had feedback processes in place for more than 100 years. These feedback processes allowed the Navy to create a culture of innovation long before World War II broke out. The US Navy became what is today called a learning organization. Unlike the Japanese military, the Navy learned to use emerging technologies such as radar to help it gain air and naval superiority. Feedback was critical in helping the officers and men learn to use these new technologies. It also helped refine existing strategies, processes, and procedures.

(It wasn’t always smooth during the war. Two exceptions were the failure to best use and interpret radar data during the naval battles off Guadalcanal and the Bureau of Ordinance’s refusal to fix the problems with Mark XIV torpedos. Nevertheless, lessons were learned, and changes were made.)

Action Reports Provide Feedback

I want to focus on one form of feedback the US Navy used to move those ideas up the chain of command, the Action Report* Because the Navy’s task forces were often at sea spread out over thousands of miles, it was seldom possible to assemble people together in a timely face-to-face meeting. Therefore, the Navy relied on written action reports, typically completed within a week or so of a combat mission or training exercise. In my research on USS Franklin, I’ve read quite a few from World War II. After a battle, a US Navy task force would see action reports written by each ship captain forwarded up the chain of command. Each would be addressed to “Commander in Chief, United States Fleet” (Admiral Ernest King during WWII). The Task Force or Task Group commander would also write one and endorse those written by the ships’ captains under his command. Air group commanders serving on aircraft carriers would also write and forward them.

Elements Of An Action Report

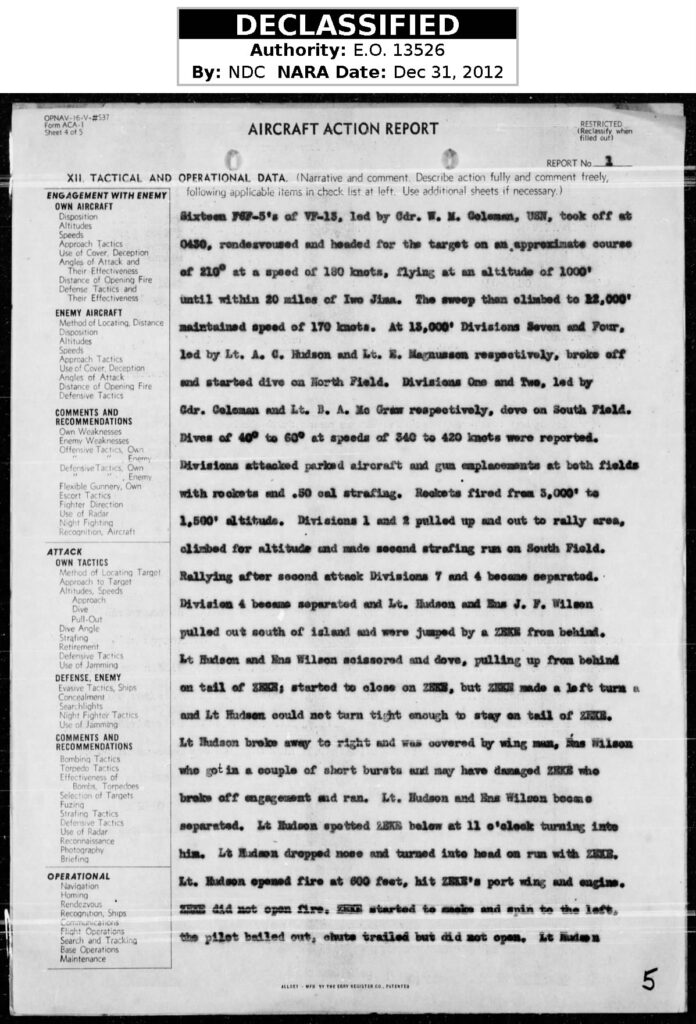

Action report templates for air groups were longer, and often, the left margins contained topics to be covered. (See image above.)

For a task force or task group, the action report sections were:

- Part I Disposition of the task force or group

- Part II Narrative summary of the events

- Part III Chronological account of the action

- Part IV Report of ordinance used

- Part V Battle damage (if any)

- Part VI Conclusions and Recommendations

- and Part VII Personnel Performance.

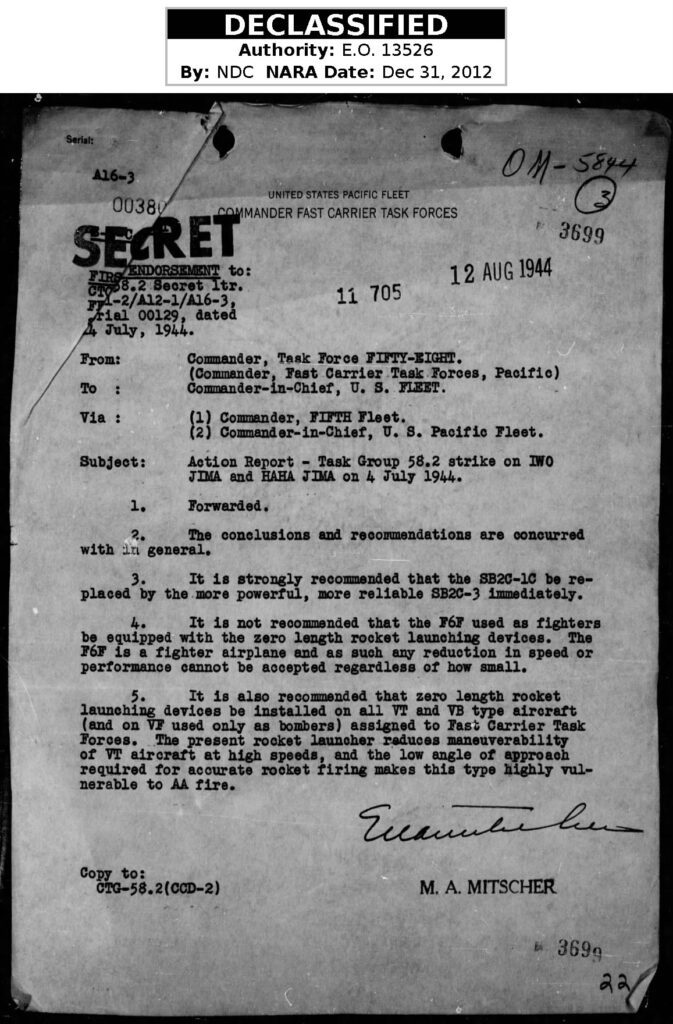

Action Report Recommendations Can Be Disagreed With

In the Task Group 58.2 Action Report for 4 July 1944, Admiral Ralph Davison and his staff drew 16 conclusions and made four recommendations. His report was forwarded to his superior, Admiral Marc Mitscher, commander of Task Force 58, who endorsed three recommendations while strongly opposing the fourth (See the image below). Even though Admiral Mitscher disagreed with his subordinate’s suggestion, he did not delete it from the report. (He did give his reason for his disagreement.)

Recommendations made in action reports throughout the war allowed the Navy to better deploy radar, Combat Information Centers (CIC), fighter direction, combat air patrols (CAP), fleet defense, and tactics, just to name a few. Feedback from action reports and through other channels helped evolve offensive strategy from single carrier task forces in 1942 to the Fast Carrier Task Force of 1944 and 1945.

The Navy also relied on other means of feedback to keep senior officers informed. It is crucial to create multiple channels for feedback, one of which can be action reports. More importantly, it’s about fostering a culture that welcomes and acts on feedback when appropriate. This commitment to the process can help your organization survive in a changing, sometimes chaotic, environment.

I highly recommend Trent Hone’s Learning War if you want to learn more about how creating learning systems helped the US Navy contribute to the defeat of the Japanese in World War II.

*These are also known as an “After Action Report” or a “Hot Wash.”

Did you arrive here via a search engine? I am the author of the forthcoming book Heroes By The Hundreds: The Story of the USS Franklin (CV-13). In addition to writing about the bravery of the crews that saved her, I will discuss the lessons we can learn in leadership and decision-making and the changes the US Navy made because of those lessons.

Feel free to follow me on Facebook. There, I am M. Glenn Ross, Author. I also write a monthly newsletter, Glenn’s Action Report, about subjects I find interesting in my research. You can sign up for it below. Feel free to leave a comment or ask a question. Thanks for reading.

-Glenn

1 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] In my research into the events of 19 March 1945 aboard the USS FRANKLIN, I have been reading various primary sources, such as deck logs, war diaries, and action reports. I am especially fascinated by the action reports of the different ship and task force commanders. (You can learn more about the purpose of an action report by reading my earlier post, How Action Reports Helped The US Navy Defeat The Japanese.) […]